Explained: What is Section 144 CrPC, imposed in Roorkee to restrict a Hindu religious gathering?

Section 144 of the CrPC: This colonial-era law, which has been retained in the Code, empowers a district magistrate, a sub-divisional magistrate, or any other executive magistrate empowered by the state government, to issue orders to prevent and address urgent cases of apprehended danger or nuisance.

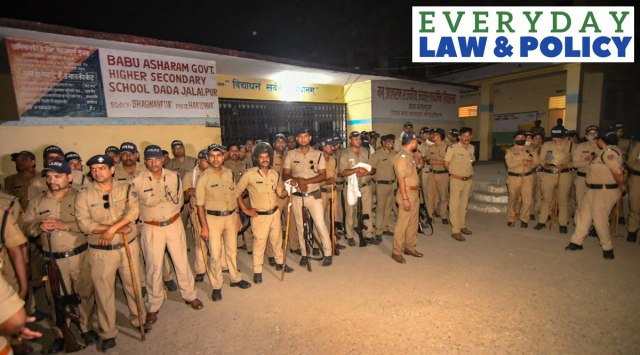

Heavy police force deployment at Dada Jalalpur a day before a Dharma Sansad by the seers, in Haridwar district, Tuesday, April 26, 2022. (PTI Photo)

Heavy police force deployment at Dada Jalalpur a day before a Dharma Sansad by the seers, in Haridwar district, Tuesday, April 26, 2022. (PTI Photo)

The administration of Uttarakhand’s Haridwar district on Tuesday (April 26) imposed prohibitory orders under Section 144 of the Code Of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973 in an area upto 5 km around a village called Dada Jalalpur near the town of Roorkee.

Section 144 was invoked after the Supreme Court instructed the Uttarakhand government to give a commitment that there would be no “untoward situation” or “unacceptable statements” during a mahapanchayat that had been planned by Hindu religious leaders in the village on Wednesday (April 27).

Incendiary speeches against Muslims have been made by Hindu religious leaders at such gatherings previously, including one organised in Haridwar in December last year.

Section 144 of the CrPC

This colonial-era law, which has been retained in the Code, empowers a district magistrate, a sub-divisional magistrate, or any other executive magistrate empowered by the state government, to issue orders to prevent and address urgent cases of apprehended danger or nuisance.

The written order by the officer may be directed against an individual or individuals residing in a particular area, or to the public at large. In urgent cases, the magistrate can pass the order without giving prior notice to the individual targeted in the order.

Powers under the provision

The provision allows the magistrate to direct any person to abstain from a certain act, or to pass an order with respect to a certain property in the possession or under the management of that person.

This usually means restrictions on movement, carrying arms, and unlawful assembly. It is generally understood that an assembly of three or more people is prohibited under Section 144.

When aimed at restricting a single individual, the order is passed if the magistrate believes it is likely to prevent obstruction, annoyance or injury to any lawfully employed person, or a danger to human life, health or safety, or a disturbance of the public tranquility, or a riot, etc.

Orders passed under Section 144 remain in force for two months, unless the state government considers it necessary to extend it. But in any case, the total period for which the order is in force cannot be more than six months.

Criticism of Section 144

Affected parties have often argued that the section is sweeping, and allows the magistrate to exercise absolute power unjustifiably. Under the law, the first remedy against the order is a revision application that must be filed to the same officer who issued the order in the first place.

An aggrieved individual can file a writ petition in the High Court if their fundamental rights are affected by the order. However, aggrieved individuals argue that in many cases those rights would have already been violated by the state even before the High Court has intervened.

It has also been argued that imposing prohibitory orders over a very large area — such as was done in all of Uttar Pradesh during the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill — is not justified because the security situation differs from place to place and cannot be dealt with in the same manner.

Courts rulings on Sec 144

While challenges were mounted against the use of the provision in the pre-Independence era as well (for example in ‘Re: Ardeshir Phirozshaw … vs Unknown (1939)’), the first major challenge in the Supreme Court came in 1961 in ‘Babulal Parate vs State of Maharashtra and Others’.

A five-judge Bench of the Supreme Court refused to strike down the law, saying it is “not correct to say that the remedy of a person aggrieved by an order under the section was illusory”.

In 1967, the court rejected a challenge to the law by the socialist leader Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, saying “no democracy can exist if ‘public order’ is freely allowed to be disturbed by a section of the citizens”.

In another challenge in 1970 (‘Madhu Limaye vs Sub-Divisional Magistrate’), a seven-judge Bench headed by then Chief Justice of India M Hidayatullah said the power of a magistrate under Section 144 “is not an ordinary power flowing from administration but a power used in a judicial manner and which can stand further judicial scrutiny”.

The court, however, upheld the constitutionality of the law, ruling that the restrictions imposed through Section 144 are covered under the “reasonable restrictions” to the fundamental rights laid down under Article 19(2) of the Constitution. The fact that the “law may be abused” is no reason to strike it down, the court said.

In 2012, the Supreme Court criticised the government for using Section 144 against a sleeping crowd in Ramlila Maidan. “Such a provision can be used only in grave circumstances for maintenance of public peace. The efficacy of the provision is to prevent some harmful occurrence immediately. Therefore, the emergency must be sudden and the consequences sufficiently grave,” the court said.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox