How an old report can pave way for central forces to stabilise Manipur

The 2010 report of the Punchhi Commission offers a way to break the deadlock in the state

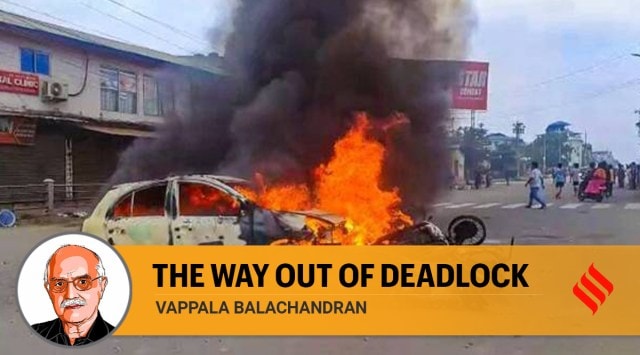

Vappala Balachandran writes: The Commission set up eight task forces to examine the Centre-state relations in depth. Their Fifth Task Force studied criminal justice, national security and Centre-state cooperation (PTI)

Vappala Balachandran writes: The Commission set up eight task forces to examine the Centre-state relations in depth. Their Fifth Task Force studied criminal justice, national security and Centre-state cooperation (PTI) An important file lying dormant with the Ministry of Home Affairs since 2010 could perhaps have provided a political solution to the current impasse in Manipur, and reduced violence. On April 27, 2007, the UPA government constituted the Second Commission on Inter-state Relations under the chairmanship of Justice (retired) Madan Mohan Punchhi, former Chief Justice of India with eminent persons like the late N R Madhava Menon, former director, National Judicial Academy, Bhopal as members. Item 2(k) of their charter was: “The feasibility of a supporting legislation under Article 355 for the purpose of suo motu deployment of Central forces in the States if and when the situation so demands.”

The Commission set up eight task forces to examine the Centre-state relations in depth. Their Fifth Task Force studied criminal justice, national security and Centre-state cooperation. The Commission submitted its report on March 31, 2010. The UPA government could not introduce constitutional changes recommended by the Punchhi Commission although it remained in office for another four years. Had the NDA government, which had an overwhelming majority in Parliament pursued the recommendations, we could have tackled many such issues like the Kuki-Meitei clashes or Maoist menace in some parts of the country in a more effective manner. The last we heard about the file was that it was discussed by the Inter-State Council’s Standing Committee (ISC) in its meetings in April 2017, November 2017 and May 2018.

An important recommendation made by the Commission was on Article 355 (Duty of the Centre to protect the state against external aggression and internal disturbance) and 356 (Failure of constitutional machinery in the state). The Commission took note of the general reluctance of political parties, especially in Opposition-ruled states, to allow the Centre to take over their elected administration even if law and order broke down temporarily. The states considered such measures as political punishment. Hence, the Commission adopted a via media.

It recommended adopting “Localised Emergency provisions” under Article 355, bringing a district or even part of a district under the Central rule. In the rest of the areas, the same elected state government would continue undisturbed: “The clarification as suggested at 4.6.02 above may also include a suitable provision allowing the imposition of the Central rule in a limited affected area, of the state, may be a municipality or a district.” Similar provisions are available in some other federations such as Australia and the United States. The commission recommended that such take over should not be for more than three months.

Another recommendation was to amend the Communal Violence Bill to include that state consent should not become a hurdle in the deployment of central forces in a serious communal riot. However, such deployment should only be for a week and post-facto consent should be taken from the state. This was to prevent a Babri Masjid-type of situation. The Communal Violence (Access to Justice & Reparations) Bill introduced by the UPA government on February 6, 2014, had to be withdrawn due to objections from the combined opposition including BJP, Samajwadi Party, CPM, AIDMK and DMK — they alleged that it went against “Federal principles”.

Had these recommendations been codified by amending our Constitution, the Centre could have taken over the administration of only the Kuki dominant areas in Manipur without disturbing the elected Biren Singh government. Considering the disrupted communications system between the elected Kuki BJP members like Paolienlal Haokip and Chief Minister Biren Singh, this would have provided a face-saving formula to the BJP government at the Centre.

History reveals that something like this was done in 1950 by the then Union Home Minister C Rajagopalachari to tackle the second phase of the Telangana insurgency. It was perhaps then the only example when the entire administration including law and order of a portion of a state was given to the Central Intelligence Bureau with a mandate to get rid of insurgents “within six months”.

During the first phase of the insurgency, the army moved into Telangana in April 1949. But it could not match the insurgents’ guerrilla warfare as its personnel had no knowledge of the local topography. In February 1950, the troops engaged in Communist operations were also withdrawn. The Communist insurgency got strengthened. That was when Rajagopalachari gave the overall command of countering communists to B N Mullik, Director of the Intelligence Bureau. His area of operations was confined only to Communist strongholds and not the entire Hyderabad state.

Mullik’s strategy was to set up platoon-strong “civil centres” near the pockets of insurgency as the primary resistance force. These were meant to protect the civil administration and instil confidence among the villagers. Fifty such centres were opened. These centres would also break the contact between Communists and guerrillas. The number was increased to 144. Nearly 8,000 Communists were arrested, and 400 guerrillas were killed. By September 1951, the movement lost steam. Part of the reason was also because the Communist Party high command had changed its strategy on militant armed struggle, following advice from Moscow in December 1950.

The writer is a former Special Secretary, Cabinet Secretariat. Views are personal