Sugar is sweet but its history says otherwise

The history of the world is inextricably linked to the history of trade, in particular, the widespread trade of goods obtained on the back of atrocities and those capable of shaping our entire monetary system. In Tracking the Trade Winds, we look at the seismic importance of gold, sugar, silk, oil and more in connecting civilisations, enriching empires and facilitating the migration of people and resources.

Sugar, a sweet good with a bitter history

Sugar, a sweet good with a bitter history Sugar has fed a global slave trade so brutal that British abolitionist William Fox, in 1787, wrote that every sweetened cup of tea was “stained with the spots of human blood”. A look at the bitter journey of sugar from India to the rest of the world’

How sugar took over the world

How sugar took over the world

In Roald Dahl’s 1964 classic, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, readers are introduced to a fantastical, wonderous world, steeped in vibrant colours, chocolate rivers, and confections that defy the laws of physics. Beneath this sugary paradise, however, lay the dark underbelly of slavery, represented in the Oompa Loompas, whom Wonka proudly introduces as real people, “imported from the deepest and darkest part of the African jungle” to work in his factory in exchange for cocoa beans. While Dahl’s story is a work of fiction (which he “de-negroed” in 1973 amidst racial backlash,) his portrayal of the Oompa Loompas is reminiscent of how slavery was rampant in the European colonies of the 19th century.

One of the sought-after products that fed slave trade was sugar. At present, sugar has a near-ubiquitous presence in the diet of humans across the globe. The widespread consumption of sugar is increasingly being perceived as a global health problem. According to the latest available data, an average person consumes approximately 17 teaspoons of added sugar per day, translating to a staggering annual intake of around 66 pounds (30 kg) of sugar per person. From spoonfuls stirred into our morning coffee to hidden doses in processed foods, our collective sweet tooth propels the colossal demand for sugar worldwide.

It is often forgotten that sugar was first discovered in India. For centuries, the large-scale production and the world-wide trade in this ‘white gold’ was inextricably linked to slavery, primarily from Africa, and then indentured labour from India. The large-scale trade in sugar historically is responsible for the settlement of the Indian diaspora in large parts of the world.

Milk and honey

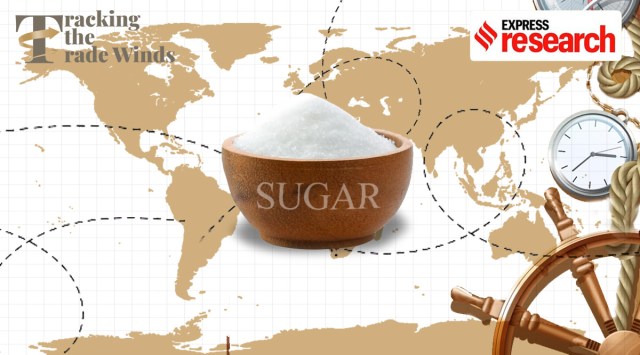

For most of human history, sweetness has been associated with divinity. From Hindu prayer rituals to the Jewish paradise of milk and honey, sweet elixirs were a symbol of affluence and often prescribed as a cure for almost every ailment. In New Guinea, where sugarcane was discovered 10,000 years ago, myths even claim that the human race was born out of intercouse between the first man and a sugarcane stalk.

Sugarcane was first discovered in New Guinea

Sugarcane was first discovered in New Guinea

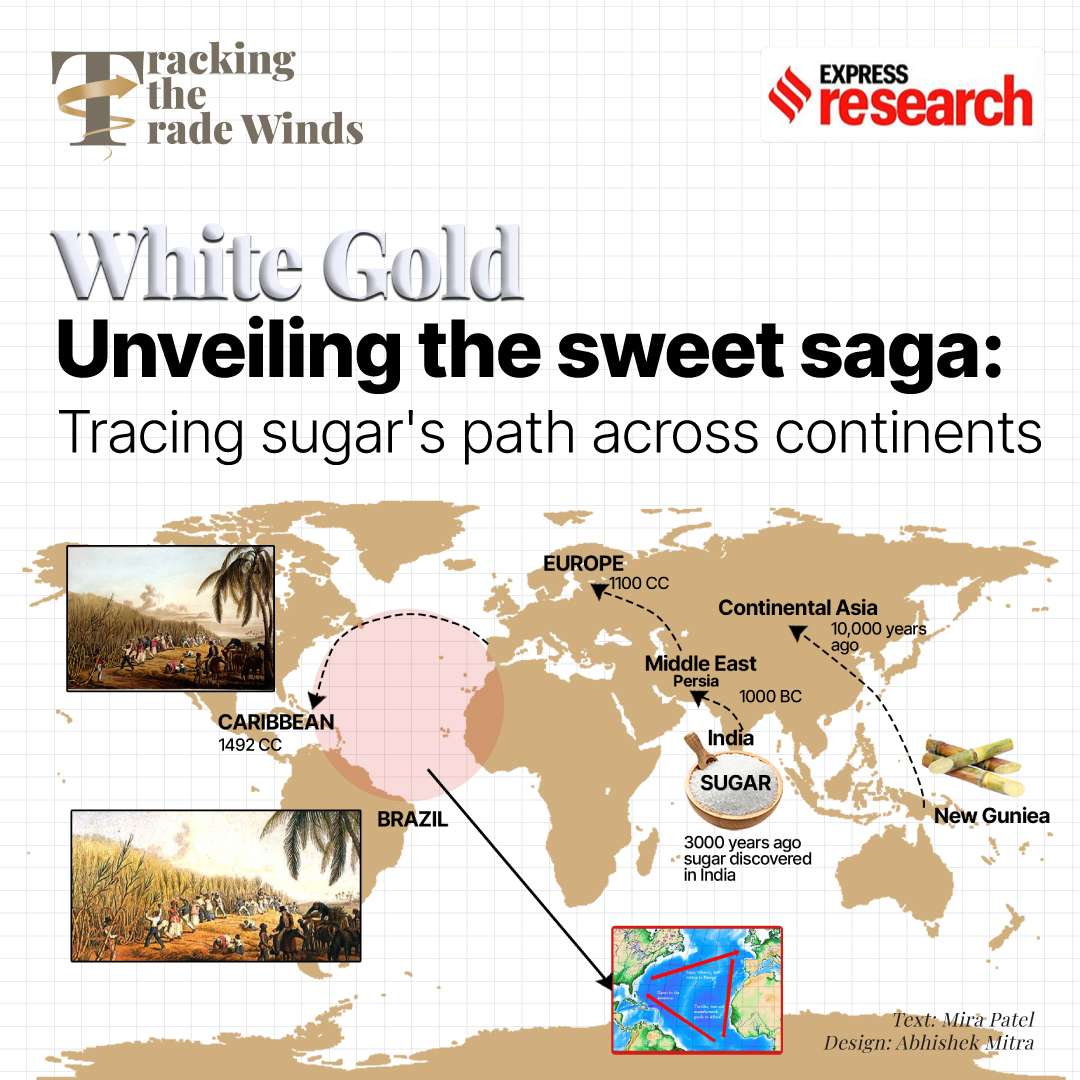

While the most popular strain of sugarcane, S. officinarum originated in New Guinea, it is believed that the earliest strain, S. barberi, originated in India. Originally, sugarcane was consumed raw, with people chewing on the stalk to extract its sweetness.

It was only 3,000 years ago, during the Gupta dynasty, that Indians first learned how to refine sugar crystals from the juice, which was monumentally easier to transport and store. The crystallisation process transformed the sugar industry.

Historian Michael Adas writes in his book, Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, that the discovery of how to turn sugarcane juice into granulated crystals was a “momentous development”. Sugar production remained a closely guarded and highly lucrative secret for centuries, generating rich profits for Indian rulers through trade across the subcontinent.

India was the first country to figure out how to extract sugar crystals from sugarcane

India was the first country to figure out how to extract sugar crystals from sugarcane

From India, the popularity of sugar amongst the elite spread rapidly across trade routes, largely, according to Adas, because of its popularity amongst Indian sailors, for whom sugar and clarified butter (ghee) were dietary mainstays. From India, travelling Buddhist monks brought sugarcane to China, a process enhanced by Indian envoys to the Sun kingdom who used sugar to cultivate relations with the Tang dynasty. Chinese documents further confirm that there were at least two missions from China to India in 647 CE, for the purpose of obtaining sugar refining technology.

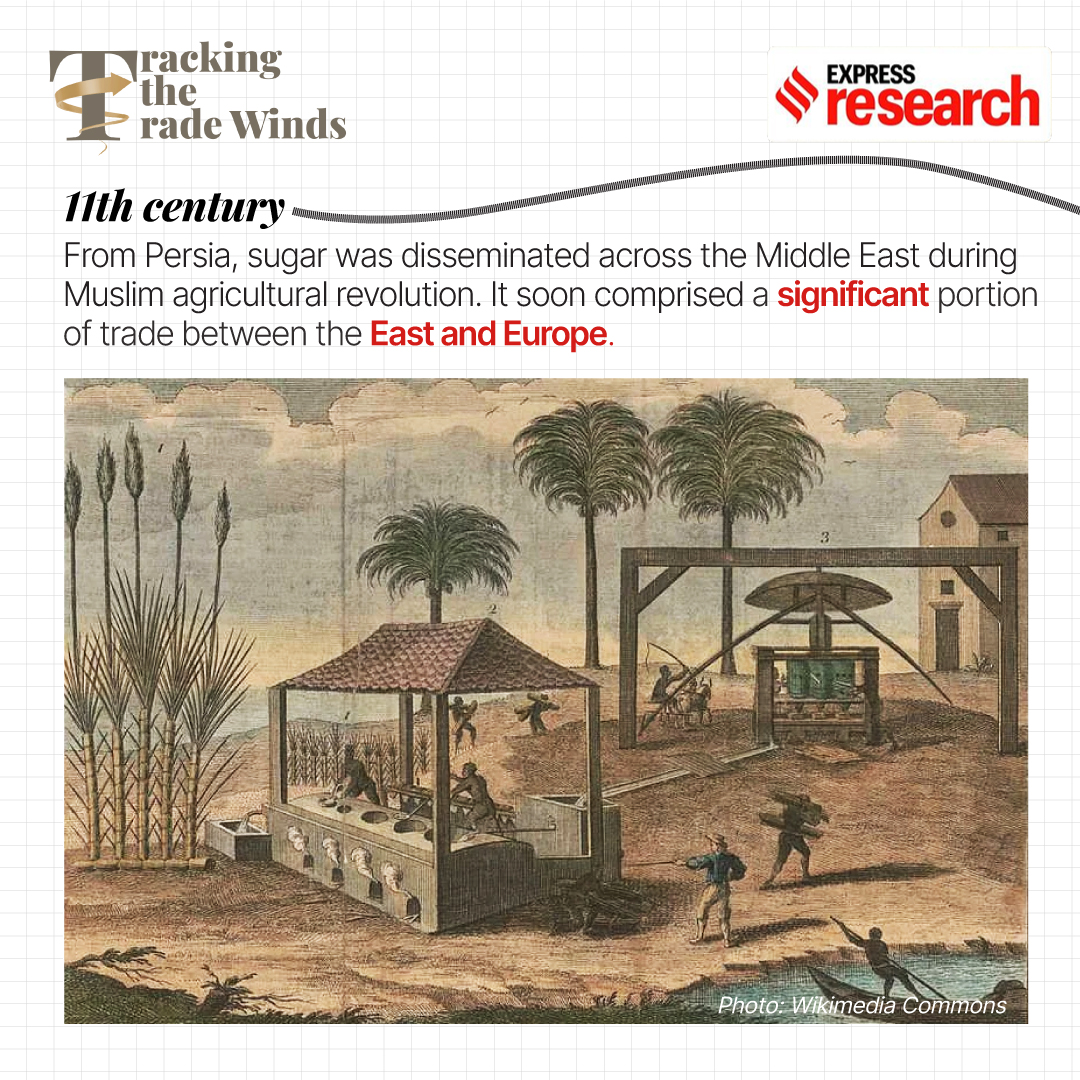

Sugar made its way into the Arab world through India as well, when in 510 BCE, Darius I, the ruler of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, invaded India and brought sugar production technology back to Persia. Sugarcane, or the “Persian reed”, was then disseminated across the Middle East during the Muslim Agricultural revolution, becoming so popular that there were believed to be entire mosques made from marzipan, a pliable paste of almonds and sugar. As the acclaimed historian Sidney Mintz wrote in 1985, “wherever they went, the Arabs brought with them sugar, the product and technology of its production”.

By the 11th century, sugar constituted a significant portion of trade between the East and Europe. However, at the time, it was considered to be a highly sought-after luxury good, exorbitantly priced due to the intensity of labour required for its production. That began to change in the 1350s, after technological improvements doubled the output of juice obtained from a single cane, incentivising European rulers in Italy, Spain, and Portugal to invest in the development of sugarcane plantations.

It was from Portugal that sugar was brought to the New World, making its way to Hispaniola (the island that hosts Haiti and the Dominican Republic), with Christopher Columbus in 1492. To the surprise and delight of Columbus and other settlers, sugarcane thrived in the tropical environment of the Americas, despite not being indigenous to the region. Noting its lucrative potential, Spanish colonisers transported seeds from Hispaniola to their colonies in the Caribbean, with the British, Dutch, and French soon to follow.

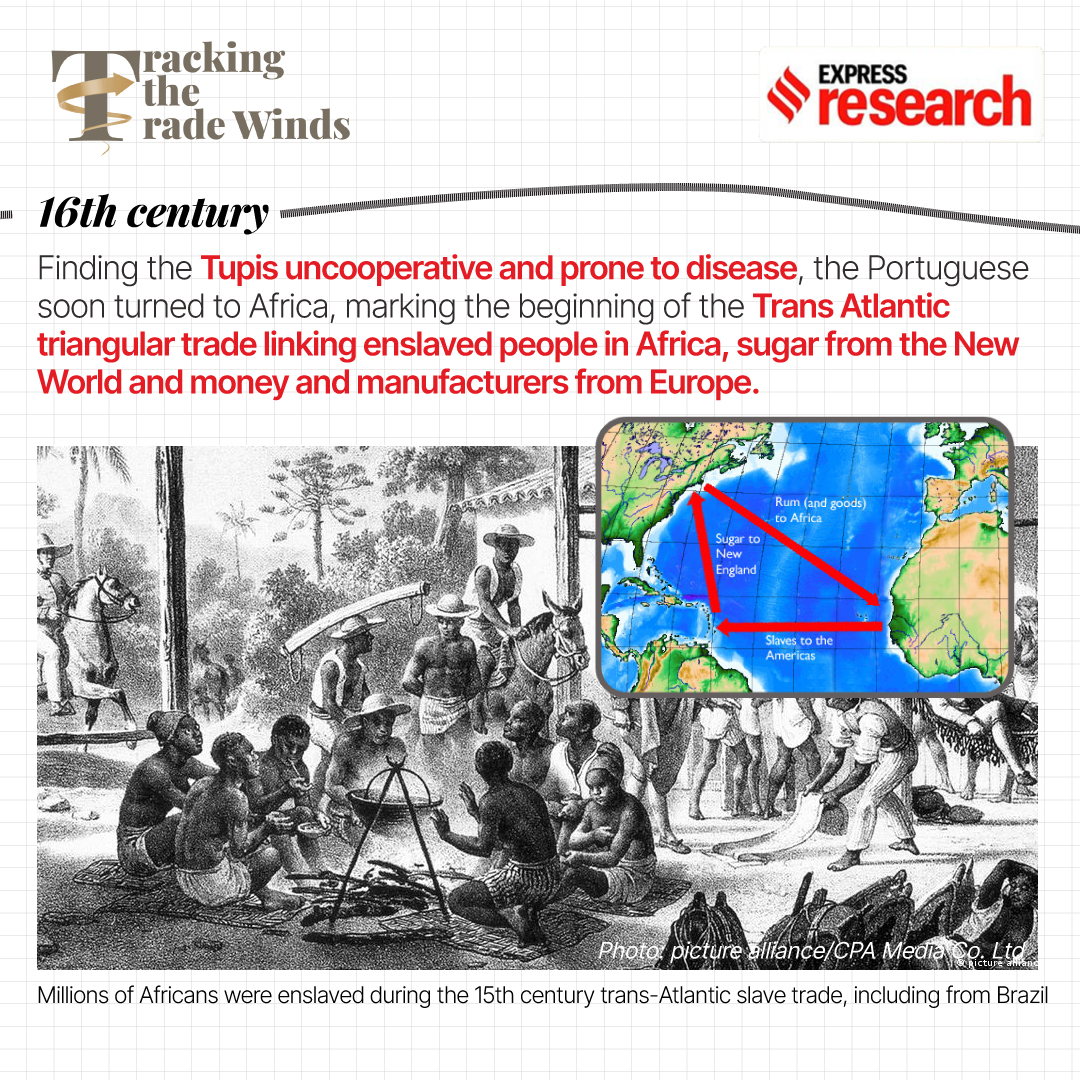

By the time the Portuguese made their way to Brazil in the early 1530s, sugar had become a household staple amongst upper middle-class European families. The Portuguese, hoping to increase production at lower costs, enslaved the local Tupi population and forced them to work in the plantations. However, the Tupi proved to be “uncooperative” slaves, attempting frequently and successfully to escape into the dense Brazilian forests they called home. Moreover, the Portuguese brought with them a host of diseases, and the Tupi, having never been exposed to them before, were prone to illness and death, leading to manpower shortages.

To combat this problem, the Portuguese turned to the African slave trade, where ships of people could be bought and sold to plantation owners across the colonies. Armed with a near unlimited supply of workers who were more resistant to European diseases having been in contact with them longer, sugar manufacturing skyrocketed.

Innovations in sugar production helped increase the availability of the good

Innovations in sugar production helped increase the availability of the good

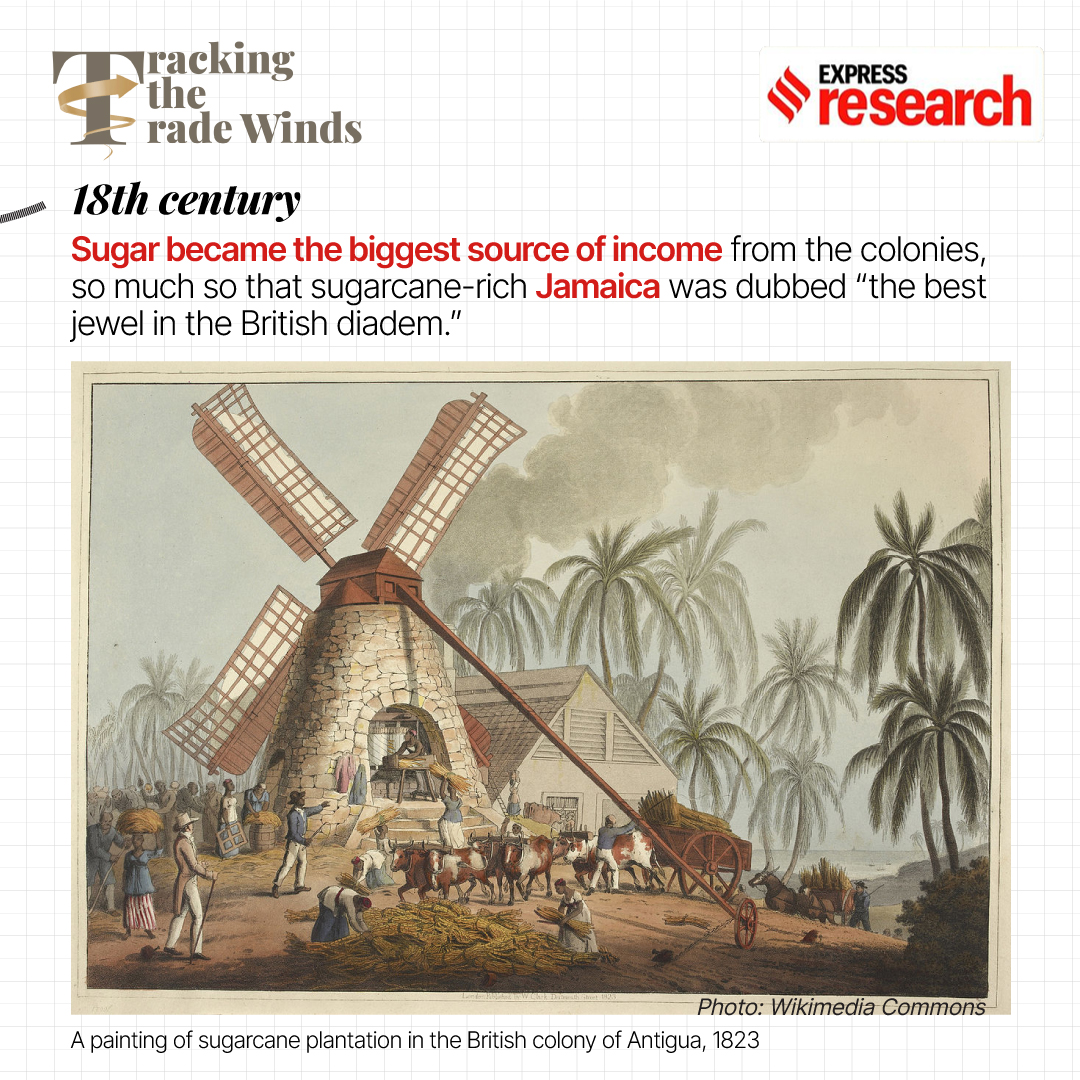

Sugar became the biggest source of income from these colonies, so much so that in the 18th century, sugarcane-rich Jamaica was dubbed “the best jewel in the British Diadem,” by British Admiral George Rodney.

Sugar plantations were so integral to the colonial machine, that, during the American Revolution, as historian Matthew Parker writes in Sugar Barons, Britain’s defence of Jamaica was given priority over the war in America. Alluding to its importance in her 2013 book, Sugar in the Blood, Andrea Stuart writes that “the Caribbean sugar islands were more than valuable to their colonial masters: they were priceless…their capacity to generate obscene profits led many to describe them as ‘the best of the west’”.

Nothing could stop the vapid pursuit of sugar. When Haiti declared its freedom from France in 1804, slaves from St Dominique were transported to Louisiana, with sugar plantations popping up across the banks of the Mississippi river. When consumers in the Netherlands protested against the sale of products obtained from slavery, the Dutch shifted production to their colony in Indonesia, where people were forced to work on plantations but were one step short of being described as slaves. When Britain blockaded France during the Napoleonic Wars, French scientists rushed to develop a sugarcane alternative, eventually resulting in the processing of sugar from beets.

It was against this backdrop of exorbitant reliance on sugar, that the transatlantic slave trade flourished.

Sugar and slavery

The first slave ships arrived in the Americas in 1505, and continued to sail into the Atlantic for more than 300 years. While slavery has been a constant in human history, it was the introduction of sugar slavery into the New World that supercharged the practice. As Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos write in their 2010 book, Sugar Changed the World, “the true Age of Sugar had begun – and it was doing more to reshape the world than any ruler, empire or war had ever done”.

Sugar was brought to the New World by the Portugese

Sugar was brought to the New World by the Portugese

Over the four centuries that succeeded Columbus’ arrival, in the mainlands of North and Central America and in the sugar islands of the West Indies, nearly 11 million Africans were enslaved, just counting those who survived the journey there. These slaves were an integral part of the triangular trade, facilitating the accumulation of wealth in European nations.

According to Harvard historian Walter Johnson, “Much of the Atlantic trade was triangular: enslaved people from Africa; sugar from the West Indies and Brazil; money and manufactures from Europe.” The system was purely financial, with little regard for human life and suffering. “People were traded along the bottom of the triangle,” Johnson states, “profits would stick at the top.”

Sugar production was also extremely labour-intensive and brutal. Slaves on sugar plantations endured grueling conditions, their high rates of mortality and physical deterioration only exacerbating the demand for even more slaves to be transported across the Atlantic. Europeans were rarely tasked with working on the fields, and the white plantation owners, according to Johnson, were often likely to be drunk by breakfast. The obligation to work lay with the slaves.

So prevalent was the association between sugar and slavery, that in 1787, British abolitionist William Fox wrote that every cup of sweetened tea was “stained with the spots of human blood”.

Sugar and Indian indentured labour

Following the abolition of slavery in the early 19th century, a substitute for the labour on sugar plantations had to be found. The British government in India enforced the indentured labour system in the mid-19th century that led to the displacement of close to 3.5 million Indians to other European colonies to meet labour requirements on the sugarcane plantations there.

Beginning in 1826, Indian labourers would appear in front of a judge to declare that they were willing to work on foreign plantations before being shipped to the same under a service contract of five years. The labourers were paid a nominal and often inadequate sum for their work, and were trapped in the colonies until their period of service was over.

The Portuguese enslaved the Tupi tribe in Brazil to work on their sugar plantations

The Portuguese enslaved the Tupi tribe in Brazil to work on their sugar plantations

Although the girmit system, as it was called locally, was overturned by the East India Company in 1839, following pressure from European colonial powers, it was reinstated just three years later. On paper, the Indian workers still had some rights, including the right to refuse service and the right to return home upon the expiration of their contracts. However, investigators found that the system was being abused, with Indians on sugar plantations suffering from a high death rate, and repatriation regulations frequently ignored.

The system regulated millions of Indians to a life of indentured servitude but such was the sway of European sugar barons, that even widespread protests could not cull the popularity of the practice. For plantation owners, importing indentured labour from India became viable because unlike the newly emancipated slaves from Africa, Indian labourers were willing to work for low wages.

The nature of the recruitment was such that mostly people from poorer backgrounds and lower castes were approached for the practise. A large number of the labourers came from the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar which had experienced acute migration in the 19th century and was battling against widespread poverty. The recruiters, locally known as ‘arkatis’, used several questionable methods to lure prospective labourers, which included at times narrating tales of prosperity in these distant lands, and more forceful methods such as kidnapping.

Sugar accounted for a significant proportion of revenues from colonies

Sugar accounted for a significant proportion of revenues from colonies

Faced with the hardships of life on the plantations, many Indians longed to return home. However, for plantation owners, their departure was inconceivable. Colonies like Mauritius offered Indian workers a gratuity of GBP (British Pound) 2 to renounce their claim to free passage home and pressured the British government into disincentivising Indians from leaving. Finally in 1852, the Government of British India changed their policy to stipulate that if an Indian working overseas did not claim their right to return within six months of the stated return date, they would forfeit that right altogether.

The success of importing Indian workers caught the attention of other colonial powers over time. The French were said to have hired Indian labour via the French ports in India without the knowledge of the British government and the Dutch traded certain properties in West Africa for the right to import British Indian subjects to Suriname. The practice was finally banned in 1917 but, as the Economist noted at the time, this was due to pressure from the Indian nationalists and declining profitability, rather than because of any humanitarian concerns.

The practice of indentured system resulted in a large diaspora of Indians in the Caribbean, South Africa, East Africa, Malaysia and Mauritius. Most of the labourers chose to not return even after the indentured labour system was banned. About two-third of the more than 34,000 Indian immigrants in Suriname, for instance, had given up their rights to free passage back to India. Experts note that a big reason for this was the absence of caste and religious divisions in the Hindustani community that took root in these regions. In his book, ‘Coolies of the empire: Indentured labourers in the sugar colonies’, historian Ashutosh Kumar notes that since a majority of the girmitiyas were from the lower castes, they were more likely to face discrimination if they returned to India. “In their villages, returnees were ostracised for having crossed the ‘black waters’ and having mixed with other castes and religions,” he writes.

Further, a local Hindustani culture also took root in the sugar plantations. In Suriname, for instance, a new language called Sarnami Hindustani took birth, which is an amalgamation of Bhojpuri and Awadhi. Currently, it is the third most spoken language in the country after Dutch and Sranan Tongo.

Sugar in the modern world

Although both slavery and indentured labour was abolished by the turn of the 20th century, for many, the ordeal was far from over. As Professor Jill Lane wrote in her 2007 essay, Becoming Chocolate, sugar production continues to be “fraught with social problems, including child and slave labour”. Human rights groups from Amnesty International to the United Nations have called attention to the appalling conditions of sugar plantation workers in Africa, India and South America. In Brazil, the leading producer of sugar in the world, forced labour and indentured servitude is still a common practice.

Sugar was one of the biggest drivers of the triangular slave trade

Sugar was one of the biggest drivers of the triangular slave trade

In 2007 alone, 288 workers were rescued from forced labour in six plantations in Sao Paulo state, and another 409 workers from Mato Grosso do Sul state. In 2018, advocacy group Fairtrade International found that 76 per cent of all cane cutters in Belize were engaged in hazardous child labour. In 2015, the American Journal of Industrial Medicine published a report which found that sugarcane workers in Costa Rica experienced heat-related stress including fever and nausea on average once a week. After the World Bank gave Nicaragua’s largest sugar producer a loan in 2006, ensuing backlash forced the organisation to investigate working conditions. They found that sugarcane workers were significantly more likely to develop kidney failure than workers in similar fields.

For consumers too, there are risks associated with sugar consumption including obesity, heart disease and diabetes. According to a report by the Brookings Institute, if the US were to introduce a tax on sugary drinks, over a lifetime, it would save an estimated half a million lives and cut healthcare costs by $100 billion. From supply to demand, white gold is and always has been stained by human suffering and abuse. Sugar may be sweet but its history is not.