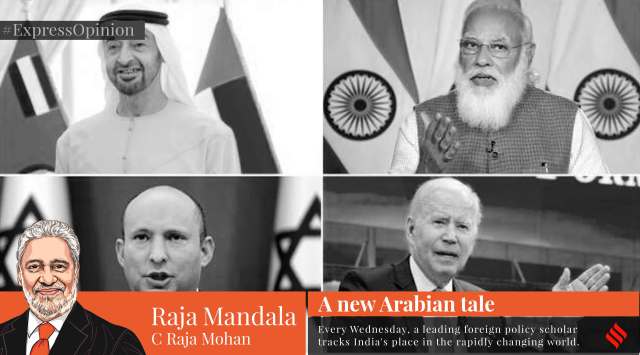

C Raja Mohan writes: How strategic convergence between US, UAE, Saudi Arabia and India can help Delhi

Seizing opportunities in the Gulf would require long overdue modernisation of Delhi’s strategic discourse, a conscious effort to change outdated narratives

Pakistan’s continuing strategic decline makes it a lot less relevant to the changing geopolitics of the Gulf. Pakistan in the 1950s was widely viewed as a moderate Muslim nation with significant prospects for economic growth. (Representational/File)

Pakistan’s continuing strategic decline makes it a lot less relevant to the changing geopolitics of the Gulf. Pakistan in the 1950s was widely viewed as a moderate Muslim nation with significant prospects for economic growth. (Representational/File) The weekend meeting in Riyadh between Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and the national security advisers of the US, UAE, and India underlines the growing strategic convergence between Delhi and Washington in the Gulf. It also highlights India’s new possibilities in the Arabian Peninsula.

The new India-US warmth on the Gulf is a major departure from the traditional approaches to the Middle East in both India and the US. In India, one of the entrenched principles of the Nehruvian foreign policy was the proposition that Delhi must either oppose Washington or keep its distance from it in the Middle East.

The self-imposed ideological taboo was broken with the formation of a four-nation grouping — unveiled in October 2021 — called I2U2 that brought the US, India, Israel, and the UAE together.

Joining hands with the US was not the only taboo that Modi’s foreign policy discarded. It rejected the notion that Delhi can’t be visibly friendly to Israel. He also transformed India’s uneasy relations with the two Arabian kingdoms, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, into solid strategic partnerships. Any proposition that India would sit down with the US, Israel and the Sunni kingdoms of the Gulf would have been dismissed as a fantasy just a few years ago. But here is Delhi doubling down with a new quadrilateral with the US, UAE, and Saudi Arabia.

The US is not the only Western power that India is beginning to work with in the Gulf. France has emerged as an important partner in the Gulf and the Western Indian Ocean. India now has a trilateral dialogue with Abu Dhabi and Paris. It should not be difficult to imagine Delhi and London working together in the Gulf soon. Britain enjoys much residual influence in the Gulf.

If India is shedding its “anti-Western” lens in the Middle East, the US is leading the West to discard its pro-Pakistan bias in thinking about the relationship between the Subcontinent and the Gulf. As Nehru’s India withdrew from its historic geopolitical role in the Middle East, Pakistan became the lynchpin of the Anglo-American strategy to secure the “wells of (oil) power” in the Gulf, to recall the evocative phrase of Sir Olaf Caroe, one of the last British civil servants to head the Indian foreign office. Pakistan was a key part of the Baghdad Pact created in 1955 along with Britain, Iraq, Iran, and Turkey to counter the Communist threat to the region.

After Iraq pulled out in 1958, the pact became the Central Treaty Organisation and moved to Ankara. The regional members of CENTO — Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey — formed a forum on Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD) in 1964. CENTO was dissolved in 1979, and the RCD morphed into Economic Cooperation Organisation in 1985. If Pakistan was central to these regional organisations backed by the West, it does not figure in the current strategy to connect the Gulf with the Subcontinent.

Pakistan’s continuing strategic decline makes it a lot less relevant to the changing geopolitics of the Gulf. Pakistan in the 1950s was widely viewed as a moderate Muslim nation with significant prospects for economic growth. It has now locked itself into a self-made trap of violent religious extremism and its political elite is utterly unprepared to lift the nation economically.

To make matters more complicated, Pakistan has drifted too close to China. As the US-China confrontation sharpens, Islamabad is tempted to align with China and Russia in the region. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s rush to Moscow when Russian President Vladimir Putin was about to invade Ukraine in February 2022 and his anti-American tirades were not the result of a maverick worldview. Recent leaks of documents from the Pakistan foreign office show that the current government might prefer to boost its “all-weather partnership” with Beijing.

As the intra-regional and international relations of the Arabian Peninsula poised for momentous change, India has inevitably become part of the new regional calculus. Contrary to the widespread perception, the US is not about to abandon the Middle East. But it certainly is recalibrating its regional strategy. In a major speech last week in Washington, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan highlighted several elements of the new US approach. Viewed from Delhi, two of them stand out. One was about building new partnerships, including with Delhi, and the other was about the integration of the Arabian Peninsula into India and the world. Sullivan promised his Washington audience that they will hear a lot more in the coming days about the I2U2 and new regional coalitions the Biden Administration wants to build with India.

It is tempting to frame India’s possibilities in Arabia as well as the incipient regional partnership with the US in terms of geopolitical competition with China. That will be unwise. Beijing is now the second most important power in the world, and its diplomatic and political influence in the region will continue to rise. Yet, Beijing is nowhere near displacing Washington as the principal external actor in the Gulf. Seen in conjunction with Britain, the Anglo-American connection to the Arabian Peninsula dates to the late 16th century. The Anglo-Saxon powers have no desire to roll over and cede the Gulf to Beijing.

The story, however, is only partly about China and the US; it is really about the rising power of the Arabian Peninsula, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Gulf kingdoms have accumulated massive financial capital and embarked on an ambitious economic transformation that will reduce their dependence on oil over the long term. They have also begun to diversify their strategic partnerships, develop nationalism rather than religion as the political foundation for their states, promote religious tolerance at home, and initiate social reform.

The story is also about India in Arabia. Emerging Arabia opens enormous new possibilities for India’s economic growth and Delhi’s productive involvement in promoting connectivity and security within Arabia and between it and the abutting regions — including Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean — and the Subcontinent. The engagement should also help India overcome the dangerous forces of violent religious extremism within the Subcontinent. The new opportunities in Arabia and the emerging possibilities for partnership with the US and the West position India to rapidly elevate its own standing in the region.

Seizing the new strategic opportunities for India in the Gulf would, however, involve the long overdue modernisation of Delhi’s strategic discourse on the Gulf and a conscious effort to change the outdated popular narratives on the Arabian Peninsula.

The writer is senior fellow, Asia Society Policy Institute, Delhi and contributing editor on international affairs for The Indian Express