Vandita Mishra writes: Kejriwal’s AAP vs Modi’s BJP — The intimate enemies

Across their many differences — a polarising politics of Hindutva is central to the BJP’s self-definition while the AAP’s calling card is a sort of ideology-agnostic solutionism — the two parties have more in common than is let on by their currently picturesque hostilities

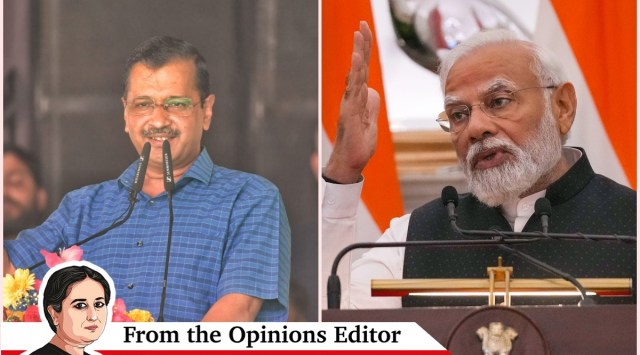

Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. (Express Photo/PTI)

Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. (Express Photo/PTI) Arvind Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party held a rally at the capital’s Ramlila Maidan today, Sunday, June 11, against the BJP-led Centre’s ordinance wresting control of services from Delhi’s elected government and it was striking how fluidly AAP, the ruling party, slipped back into the role of challenger. If you closed your eyes and only listened to the rhetoric that filled the ground, of “bhrashtachaar (corruption)” and “aandolan (revolution)”, “taanashahi (despotic rule)” and “ahankaar (arrogance)”, it was easy to forget that the AAP is actually the government in Delhi.

There was Kejriwal, recalling the birth of the AAP in that very maidan, 12 years ago, in the Anna Hazare-led movement against corruption. There he was, telling, with great relish and flair, the story of the “chauthi paas raja (king who studied only till class 4)”, who makes disastrous decisions like demonetisation, and is also “dostbaaz”, protects his corrupt friends, and must therefore be immediately ousted by the people.

The gusto with which the AAP plays party-under-siege in government, is matched only by the relentless enthusiasm with which the BJP projects itself as flagbearer of constant revolution after nine years of being the Establishment.

The fact is, across their many differences — a polarising politics of Hindutva is central to the BJP’s self-definition while the AAP’s calling card is a sort of ideology-agnostic solutionism — the two parties have more in common than is let on by their currently picturesque hostilities.

I remember spending one August night in 2011 at the Ramlila Maidan, as part of this newspaper’s coverage of Anna’s fast for a Lok Pal. In the concluding hours of Day 1, there was an air of excitement and festivity, and the dark was pierced by scores of twinkling phone screens held aloft by the young, the urban and the restless.

They were taking selfies, recording their presence and participation in a moment that seemed to them to be larger than themselves. Now, 12 years later, Kejriwal began his speech at the same ground by exhorting his audience to bring out their phones, switch on their cameras, go live on Facebook, communicate his message far and wide.

In this, too, the AAP is a lot like the BJP — like Modi’s party, Kejriwal’s outfit has been agile in seizing the political opportunities offered by the reshaping of medium and message in an era of communicative abundance.

The Ramlila maidan is itself a point of intersection for the trajectories of the BJP and AAP. Even as this storied maidan in the nation’s capital cradled the movement that later became Kejriwal’s party, it is also a milestone in the rise of the Modi-BJP. The Anna movement laid the ground for the rout of the UPA 2 government, painted as scam-riddled, but the electoral benefit of that mobilisation was reaped in 2014 by the leader from Gujarat whose appeal was that he re-energised the BJP’s old Hindutva base, while playing “outsider” to the discredited Delhi establishment.

Subsequently, after the emergence of AAP as a political party, Kejriwal has enacted the same role to the hilt — his “outsider” plank was crucial to his party sweeping Punjab, a state faced with multiple crises where the people had tired of the long-running alternation of the SAD and Congress. And if Sunday’s performance at Ramlila maidan was indication, it is a role he harks back to with continued enjoyment.

As the BJP and AAP duel it out in Delhi and other arenas, therefore — last year, the AAP opened its account in Gujarat, and in recent days Kejriwal has been travelling and meeting leaders of parties across the country to drum up support against the Centre’s peremptory Delhi ordinance — it is impossible not to mark their intimate enmity.

This also means that, despite their several differences, they also face some similar challenges — two, in particular.

One, both need to tread most warily on corruption — the AAP because of the circumstances of its birth, and the BJP because of the circumstances of its rise.

Even if the BJP’s rout in the recent Karnataka election was not all because of “corruption”, it showed how other discontents can come together and trip it up in its name, despite Hindutva and in spite of Modi. In 2014, the BJP had made the UPA’s alleged “corruption” a stand-in for the old order and status quo that it promised to upend and uproot. In Karnataka, this year, the Congress had its revenge — now its allegation of the “40 per cent commission” government, its campaign’s centrepiece, became political short-hand for the all-round failure of the lustre-less Basavaraj Bommai government. (The Congress did not really lock horns with the BJP on Hindutva in Karnataka — its promise to ban the Bajrang Dal came only as a last-minute addition).

In turn, the BJP recognises the AAP’s special vulnerability on corruption — that is why its attempts to corner that party by letting loose the ED-CBI on it, that is why the prolonged jailing of senior AAP ministers, Manish Sisodia and earlier Satyendar Jain, for “scams”.

Two, both parties must, at some point, deal with the fact that the penchant for playing victim while being in power could have diminishing returns. At the very least, there is an inherent tension in the dual role play.

For instance, how long can the BJP play disruptor and change-maker as it goes about setting down a permanent “eco-system” of its own on the ground? How can the party that has built a new Parliament, a Ram temple, and one that is even redeveloping the prime minister’s school in Vadnagar as a destination for state-sponsored pilgrimage for school children, rail against a “dynasty” monopolised “eco-system”?

There is tension between the rhetoric of change and the practice of installation, between claims of disrupting the status quo and the congealed reality of personality cult, be it of Kejriwal or Modi.

The AAP is a much smaller player, and it is also the one with a far more legitimate grievance — the BJP-led Centre has used mostly foul means to shrink the space for manoeuvre of Delhi’s Kejriwal government. But that tension may be waiting to catch up with the BJP.

Or not. It may be that Modi’s party proves to be agile enough to see the danger and find ways to address it. It has already shown itself as deft at putting together layered appeals, and managing contradictory impulses within them.

Till next week,

Vandita

Must Read Opinions from the week

– Priya Ramani, “Dear Vinesh, Sakshi, Sangeeta’, June 10

– Editorial, “Mumbai dogwhistle”, June 10

– Sanjay Srivastava, “The idea of women wrestlers”, June 8